The Cold War in Videogames Part 2: The Tropico Series

Western Liberal Ideology Winds Up Obscuring The Realities of Enacting Latin American Sovereignty During the Cold War

This is a sort of follow-up to my previous post, which is about Call of Duty Black Ops Cold War. In it, I go over the basic concepts of what the Cold War was, so if you’re unfamiliar with the concept I recommend you go check it out. In this post, I will be discussing the portrayal of the time period in a very different sort of videogame: the city-building strategy series Tropico.

1-The Tropico Series.

With the exception of Tropico 2, which is about pirates, these games are all set in a non-specific part of the Caribbean and have you ostensibly playing as the dictator of a small island nation. I say “ostensibly” because in practice the player is in control of, at the same time, more things that the head of State would presumably do (down to placing individual farms) and, yet, somehow also less than what would be, in my opinion, needed for full immersion. The games can all be broadly categorized as “strategy” titles, more specifically of the “city builder” subgenre that was pioneered by games like Stronghold and that has had something of a revival after the onset of the indie revolution.

A city builder game is characterized by having the goal be to expand a human settlement. Unlike other popular strategy games like the Age of Empires series, in city builders the player doesn’t necessarily control individual “units” but rather places different buildings and markers along an allotted territory in such a way that will make a given set of factors interact and produce a favorable outcome. One of such factors can be population, but it can just as easily be ground fertility, weather, zoning ordinances, and so on.

I’ll cop to the fact that I’m personally not a fan of the genre. In fact, I was recently disappointed when I bought a game called Dawn of Man, which deals with a personal interest of mine (prehistoric times), only to find out it’s a weird sort of city builder that extends the playable period into the Bronze Age, losing the focus on pre-civilized survival that drew me in. The most notable city builders are, of course, the games belonging to the storied SimCity series, and its spiritual successor Cities: Skylines. I have never played those games and don’t intend to, since, as I’ve said, I don’t really like city builders. In fact, I’ve come to find that the Tropico series has endeared itself to me solely on the basis of its setting and flavor, despite its actual gameplay mechanics.

As the title of this post must have tipped you off, the Tropico series deals with the topic of the Cold War. I will speak about my experience with the series, which is limited to Tropico 3 (2009) and Tropico 4 (2011). If somehow Tropico 5 and 6 break wildly with the conventions I am about to discuss, I am not aware of it. But I doubt it, since all the promotional material I consulted seemed to center around the new ways in which you can develop your island nation in the modern era, such as an elevated overpass. Needless to say, this was not enough to convince me to buy these latest titles, especially since it doesn’t deal with the topic that interests me most (the portrayal and translation into game mechanics of the Cold War).

Something that is notable about this game and that it does deserve credit for is that it simulates politics, at least to an extent. Your population is divided into political factions and these factions can see your rule favorably or unfavorably depending on what edicts you proclaim or, more frequently, what structures you build. Their opinion is important, as unrest will translate into either the presence of armed rebels, strike activity, coup attempts or an electoral defeat if you decide to make your country democratic. There are advisor characters that will lobby you on behalf of the different factions (with dialog that aims for funny but mostly falls short) and you can also increase the size of a given faction either through completing specific advisor requests or by investing in an edict.

Now, I will lay out some additional Cold War concepts that are important for understanding the games’ particular scenario.

2- Cold War, Revisited.

As I said on my previous post, the Cold War was a global phenomenon that shaped every aspect of daily life. This is especially true on a political and public administration level, where the tensions of the geopolitical rivalry between the US and the USSR were more strongly felt. Governments worldwide were pressured by either power into doing their bidding, and the diplomatic corps and intelligence agencies of the superpowers had influence over everything from the drafting of legislation to cabinet appointments.

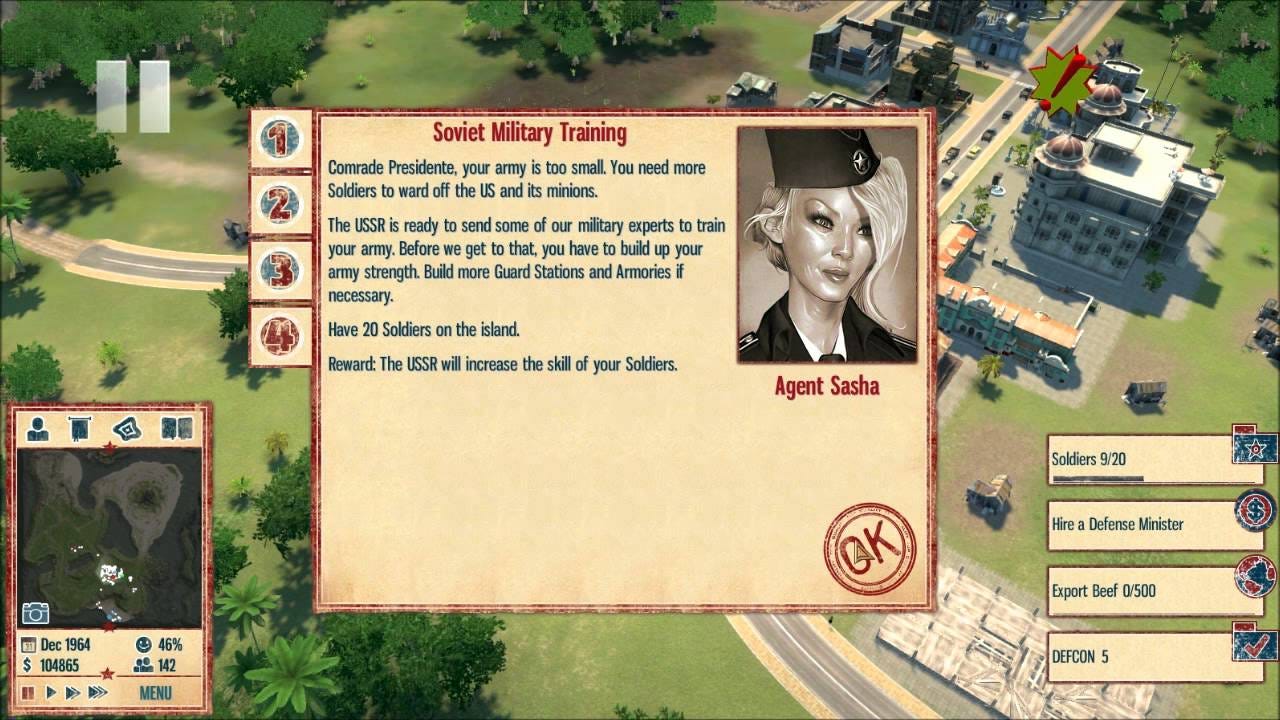

That is not to say, of course, that these countries did not themselves benefit from their relationships with the major powers: everything from military equipment, to advanced industrial and agricultural machinery, to training for the military forces and even intelligence briefings was supplied by the superpowers to foreign governments (and the factions within those governments, and the factions outside of government) in order to help them achieve their strategic goals. Many countries in fact made it their business to foster good relationships with both nuclear powers in order to try and extract benefits from both, most notably as part of the Non-Aligned Movement, an informal organization of countries that included, hilariously, Fidel Castro’s Cuba.

It is impossible to continue laying out the “ground rules” of the Cold War without bringing up a major thinker of the period: Chairman Mao Tse-Tung, head of the Communist Party of China and leader of the successful revolution which created the People’s Republic of China, the State that controls the Chinese mainland to this day. He was not the first to coin the term “third world”, but his is certainly the most relevant version of the concept for this post. In Mao’s conception, the “first world” is the Western Capitalist world, consisting of Western Europe and the United States, the countries where capitalism originated and that have historically benefited from colonialism. The “second world” is the Soviet-aligned Socialist bloc, consisting of the USSR and its allied countries in Eastern Europe. These two worlds struggled against each other for control of the “third world”, the poorer, historically colonized countries where most of humanity resides. In contemporary jargon we would call these regions “the global south”, as the lack of a “second world” to rival the first does away entirely with the Maoist framework.

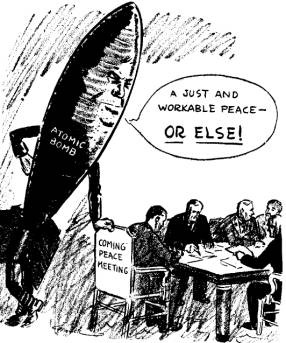

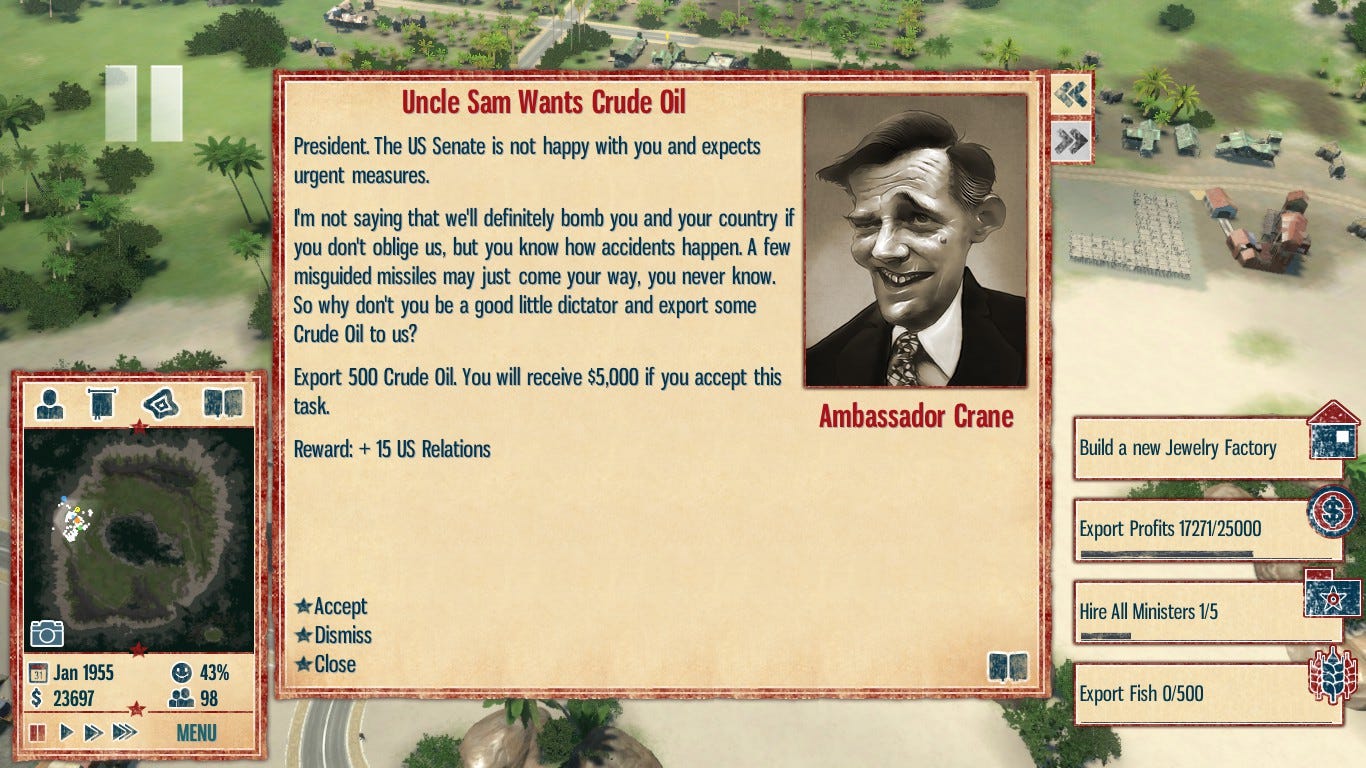

Finally, it is important to note that, while the USA and the USSR both preferred to exert their influence using what is known as “soft power” (basically, all the means of international power and influence that don’t literally include the use of force), they were not above using their militaries to step in and defend their spheres of influence through brute force when they deemed it necessary (and, of course, when this did not put them at immediate risk of direct confrontation with the other power; remember, MAD determines everything). The United States did this much more often than the Soviet Union, but the USSR is also guilty of what the Maoists would call “social imperialism” when it intervened in Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Afghanistan in 1979.

3- The Cold War in the Tropico Games.

Now that we’re up to speed on the basic tenets of the Tropico games and some additional concepts about the Cold War, we can finally discuss the ways in which this setting is portrayed in the series. In both Tropico 3 and 4, there is a sort of relationship status meter that numerically tracks your standing with either power. The meter goes up or down depending on a number of factors, such as which countries you trade with, which public policies you choose, or whether or not you spend money on edicts or embassies to directly foster the relationship with either the USA or the USSR.

This meter determines the amount of direct foreign aid you receive from either power every year (obviously, time is sped up considerably during play and you can make it go even faster) in the form of cash. This is already a departure from reality, since only the United States was in a position to give out actual money, the Soviet Union having to make do with giving material aid.

In addition to that, you can also choose to carry out specific tasks required of you by characters that are either domestic advisors aligned with either power (building public interest housing like the local communist suggests endears you to the Soviets, developing industry like the businessman wants gets you closer to the States) or outright literal agents of that foreign government.

Before I continue, I must say that this brief write-up probably makes the mechanics at hand sound way more compelling than they actually are at the moment of play. This has to do with the limitations of the city builder genre, in which you, the player, literally control the placement of every building in the country. The only structures that appear “organically” are shantytowns, a result of a lack of affordable housing. What this leads to is that there is no business establishment, no business class per se, only a “capitalist” faction among the many that make up the population and that only comes into play if and when you hold elections.

There is also, sadly, no simulation of foreign investment or even presence other than the embassies of Tropico 4 and the military base, an upgrade you can build in Tropico 3 to secure yourself from invasion, which is a possible fail-state that triggers as a result of your relationship with any one power being too bad (yes, this means that you can, in fact, get your small Caribbean nation invaded by the Soviet Union in Tropico 3). Public policy, represented in Tropico 4 as articles of the Constitution, is only a set of stat modifiers for your buildings, and doesn’t feel like something that’s tangibly affecting your citizens. Overall, I would caution the reader not to get drawn in, like I have, just for the flavor, and to keep in mind that in practice these games are not a breathtaking play experience.

Foreign military bases are only an option in Tropico 3, which means that you are never safe from invasion in Tropico 4. While I do appreciate that a good enough security apparatus can lead to you knowing the civilian identities of all rebel fighters, so that you can pre-emptively arrest them, exile them or even shoot them dead in the street (something that is remarkably true to life), it is impossible to completely wipe them out, especially since none of them adopt the far more common strategy of abandoning their ordinary lives and setting up base in a rural area. While it would perhaps be comforting to be romantic and say that the spirit of rebellion can never be snuffed out, the fact of the matter is that, historically speaking, most insurgencies are unsuccessful and most regimes stay right where they are even when faced with fierce opposition. I bring this up not because I’m a stickler for accuracy (alright, not just because of that) but also because what both this and the invasion mechanic lead to is that you’re stuck in centrism, forced into realizing that the only sensible choice is to play nice with both superpowers to avoid either of them invading you and attempt to be a mixed bag, which is odd since you are, in practice, a hyper-centralized veritable palace economy structured around the dictates of a single person.

Clearly, the Tropico development team is not ignorant of the Cold War. To make an incentive structure that has non-alignment as its most rational choice with the better outcomes is to already propose a thesis about what the Cold War was and what the best way to navigate it is. Interestingly, this course of action was only really ever afforded in Latin America to Mexico, a country that had a revolution in the early 20th Century and therefore an uncharacteristically strong State, and, even then, this relatively neutral status included considerable collaboration with the United States in hunting down its own domestic Communist revolutionaries. In truth, the path of non-alignment was a more feasible proposition for countries in Africa, the Middle East or Asia. It’s not for nothing that Latin America was often referred to as the USA’s backyard.

In 1970, Salvador Allende was elected President of Chile after running on the Popular Unity ticket, which included his own Socialist Party as well as the Communists. Given that an actual country is not a city builder videogame, however, he did not have direct control over the entire economy, and soon the economic elite of his country set to work sabotaging him and collaborating with the CIA, the Pentagon and the State Department towards the goal of overthrowing his government for the crime of looking out for the interests of the majority as opposed to those of the elite. One of the most retold legends of the Cold War says that when Fidel Castro visited Chile in 1971 he warned Allende to get rid of a notable military officer who was quickly rising through the ranks, a man by the name of Augusto Pinochet. Allende ignored this warning, insisting as he usually did that the Chilean army was loyal and committed to upholding the institutions of democracy. In 1973, Pinochet overthrew Allende and set up a military government that lasted 16 years (one that was formed on the premise of saving Chile from communist tyranny, no less) and carried out a brutal persecution of suspected communists and their sympathizers.

A military coup is not simply a matter of having the support or not of the military. It is a complex operation that requires the coordination of many different actors, like the economic elites, trade unions, the media, religious institutions and, more often than not, foreign intelligence and diplomatic agents. The fact that Tropico is limited by the formula of the city builder genre means that we are denied all of this complexity, but I don’t just bring up Allende because of this. I specifically mentioned Castro’s unheeded advice to him because it links up nicely with the topic of how Fidel avoided a similar fate, and that was to do away with the business class entirely, expropriate all aspects of the economy and thereby deny the United States of its most powerful allies in a foreign theater.

In my last post, I brought up the 1954 Guatemalan coup against President Jacobo Árbenz. Árbenz wasn’t a communist, but he did have nationalist designs on how best to use the land that was sitting idly by being accumulated by the American-owned United Fruit Company. The fact of the matter is that, during the Cold War, a Latin American country didn’t have the option to sit halfway between Communism and Capitalism, it was forced to choose, and it if was going to choose anything other than full submission to American business interests then it had better be ready to defend this choice by force of arms, a lesson that the Nicaraguan Sandinista Socialists would also come to learn in the 1980’s as they defended themselves from US-backed death squads known as the Contras. Governments that defied US business interests (and their local partners in the domestic elite) were time and again overthrown with violence, and the only way to change the status quo was to organize and arm the sectors of society that were discontent with that state of affairs.

None of this is possible to do in the Tropico games. In fact, I would go as far as to say that the choice to make “third way” politics the de facto “right answer” is informed more by the ideological tenets of American liberalism than by an objective analysis of Latin American history. It is a deeply capital-D Democratic way of looking at things: why choose between the extremes of the Cold War when you could try to get along with both sides? The answer, of course, is that the United States will apply all possible pressure on you, up and including literal armed invasion, for daring to defy its interests in its own backyard. Amenable as the thought of going “third way” might be, it is simply out of touch with what the reality was for the countries of the region at the time. In order to portray this reality, of course, one would have to make a different videogame, one that was not limited by the conventions of the city builder genre, or that, in any case, expands greatly upon them.

4- In Closing.

I do want to give the Tropico series credit for attempting to discuss and portray the Cold War, even if its humor is bad and its message is ultimately muddled by a particular strain of US-centric political thought. It is one of the few games I can name that actually tries to talk about this time period and translate its complexities into game mechanics in an effort to better portray it. I certainly think it’s more successful at this than Call of Duty Black Ops Cold War, and I think that in the off chance that there is anyone else out there also interested in both videogames and the Cold War this series is a must-play for the effort it puts forward. Nevertheless, it doesn’t quite satisfy me, and even its most diehard fans can probably agree that any work of art is always perfectible, and, in that sense, never finished.

I have decided that this impromptu series is building up to something. I will eventually review one of my favorite games, Hidden Agenda, which is, in my estimation, the best portrayal of the time period in videogames so far. Until then.

Thank you for reading.